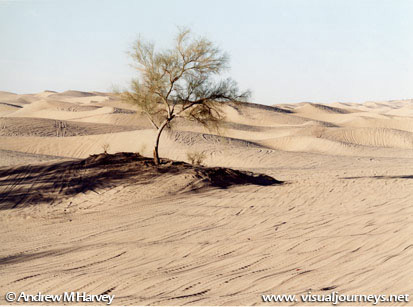

The Algodones Dunes Rise to almost 300 feet above sea level making them the tallest dunes in the southwest.

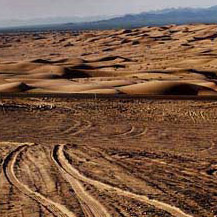

Helianthus niveus, ssp. Tephrodes - Lives at the Algodones Dunes and nowhere else on earth. This plant is rare and threatened by the unregulated use of ORVs.

It is estimated that almost 2 million off-roaders drive on the dunes every year and leave behind over 15 tons off litter in the sand.

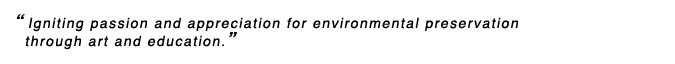

The vegetated Algodones Dunes Wilderness (background Stands in sharp contrast to the ravaged open vehicle play area (foreground) where no vegetation can be seen.

A vehicle closure at the Algodones Dunes designed to protect dunes plants and animals is ignored by this off-roader whose trespass killed a Colorado Desert Fringe-Toed Lizard. (see injured lizard).

This Colorado Desert Fringe-Toed Lizard (Uma notata rufopunctata)lies dying: its spine was broken after being run over by an ORV driver ignoring important vehicle closures at the Algodones Dunes.

Night time festivities at the Algodones Dunes resulted in both serious injuries and deaths of dunes revelers. Imperial County closed competition hill in 2003 which has pushed party goers deeper into the fragile dunes.

Thousands flock to Competition Hill for nighttime revelry. The impact caused by the fires, gasoline, and tires in the sand has made it uninhabitable for most dunes life.

Looking towards the eastern fore dunes. Vegetation Flourishes in this temporarily protected area.

Astragulus magdelenae var. peirsonii is endemic to the Algodones Dunes and is listed as threatened under the federal endangered species act

Off-road enthusiasts from all over the United States bring their RVs and ORVs to the Algodones Dunes for weekend recreating. On peak weekends the Algodnes dunes becomes one of the largest cities in the state with hundreds of thousands of visitors and tens of thousands of RVs.

This rare beetle lives only at the Algodones Dunes and at nowhere else on earth. Biologists believe it should be listed as threatened under the Federal Endangered Species act. It is threatened by ORV use at the Algodones Dunes.

Some weekends attract almost 200,000 ORV enthusiasts. In this photo no sand is left un-touched by tires.

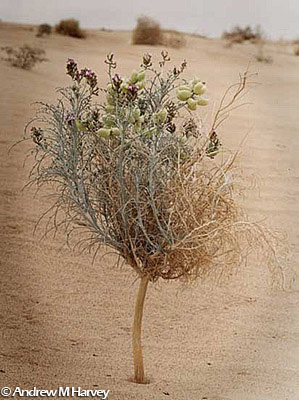

Off road activities threaten important microphyll woodlands including this Palo Verde tree at the Algodones Dunes.

Pholisma sonorae Is a rare and edible dunes plant he Algodones Dunes Rise to almost 300 feet above sea level making them the tallest dunes in the southwest.

The Algodones Dunes

Photographs by: Andrew M. Harvey

The Algodones Dunes, also known as the Imperial Sand Dunes, are a strikingly beautiful sand dune system located in Californiaís Eastern Imperial Valley. These dunes run in a northwesterly direction from Mexico near the Arizona border, towards the Salton Sea, and travel along the eastern edge of the Imperial Valley's agricultural region. At 40 miles long and averaging 5 miles wide, these dunes rise up from the California desert floor to over 300 feet in height, making them the largest sand dunes in California. The dunes are arid, with rainfall averaging less than 2 inches annually and summer temperatures rising above 110 degrees. October through May is cooler, making this an ideal time to visit the Algodones Dunes. The Dunes can be easily viewed from interstate 8 while driving between Calexico, California and Yuma, Arizona.

The Algodones Dunes were created by the prevailing wind blowing sand eastward from the Salton Sink during dry periods. This process continues today, pushing the dunes southeast one foot each year. Many scientists believe that the sand of ancient Lake Cahuilla is the sand that now forms the Algodones Dunes. Lake Cahuilla was created by the meandering Colorado River that would sometimes change its course from the Sea of Cortez and travel north, depositing both sediment and water in the Salton Sink. The water from the river would be trapped in the Salton Sink thus forming Lake Cahuilla. At times this lake would cover much of the region including the Coachella, Imperial and Mexicali valleys. The last lake Cahuilla was formed in the mid 1400ís.

The word Algodones comes from the indigenous Quechan people, who used to traverse the dunes from lake Cahuilla to the Colorado River. These people would often stop in the dunes to harvest the edible dune plant known as Sand Food (Pholisma sonorae). Now considered to be a rare plant, Sand Food is a parasitic feeder tapping the roots of host shrubs to get its food.

Many plants and animals make the Algodones Dunes their home. The plants that live in the dunes have evolved by developing root systems capable of reaching deep for water and supporting the plant in the unstable and constantly shifting sand of the dunes. It is surprising to note that the dunes are capable of retaining enough moisture beneath the surface of the sand to support the diverse life found there.

The plants and animals pictured in this exhibit are all hardy species, having adapted to both heat and drought in one of the harshest environments on earth. The dunesí plants provide shelter and food for many of the dunesí animals. Both plants and animals depend on each other for their survival.

A number of the species that live at the Algodones Dunes are considered to be rare and threatened with extinction. These include: Sand Food (Pholisma sonorae), the Flat Tailed Horned Lizard (Phrynosoma mcalli), the Andrewsí Dune Scarab Beetle, Peirsonís Milkvetch (Astragalus magdalenae, var peirsonii), and the Algodones Dunes Sunflower (Helianthus niveus, ssp. tephrodes). All of these plants and animals depend on the Algodones Dunes for their survival. Peirsonís Milkvetch and the Algodones Dunes Sunflower can be found only at the Algodones Dunes and nowhere else on earth; these are called endemic species.

The Algodones Dunes are a magnet for Off Road Vehicle (ORV) enthusiasts. The height, beauty and remoteness of the area attract more than 100,000 riders on peak weekends. Biologists fear that such heavy use of this fragile ecosystem by motorized vehicles will destroy the dunesí ability to support the species that live there. In the case of the Peirsonís Milkvetch and the Flat Tailed Horned Lizard, further harm would likely lead to the extinction of both these species. In November of 2000, the Bureau of Land Management (BLM), responding to a lawsuit brought to protect the Peirsonís Milkvetch, closed 49,000 acres of the Algodones Dunes to Off Road Vehicles to protect the Peirsonís Milkvetch. This decision insured that 54% of the Algodones Dunes would be protected for habitat while still allowing off road enthusiasts to drive on the remaining 46%.

The vehicle closure opened up the opportunity for many recreational activities including hiking, photography and bird watching. The large number of ORVís combined with limited visibility in the dunes had made such activities dangerous in the past.

The vehicle closure enabled me to safely travel overnight into the central dunes and take many of the photographs that you see in this exhibit. In April 2002, I was informed that the BLM is reconsidering re-opening the vehicle closures to ORVís. This decision could very well make the opportunity to hike within beautiful vistas of windswept sand, like you see pictured here today, a thing of the past. I fear for the dunesí plants and animals because, with the proposal to re-open the vehicle closures, comes the danger of losing these marvelous species and the species that depend on them forever.